Kretinga קרטינגה

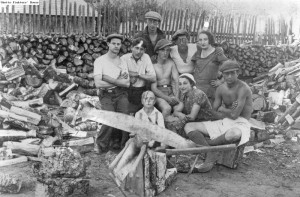

The Shtetl of the Gillis Family

Kretinge, Kretynga, Crottingen, Krottingen, Krettingen,

Кретинген, Кретинга, קרעטינגע, קרעטינגען

Kretinga - The History of a Shtetl

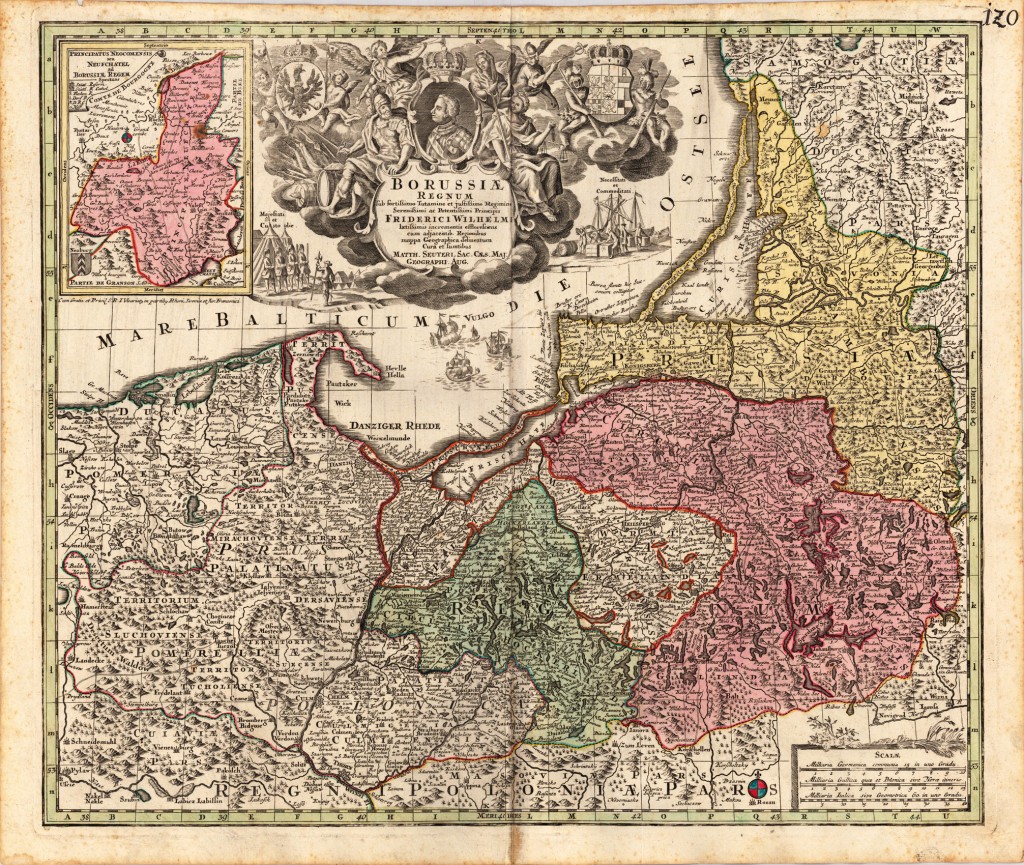

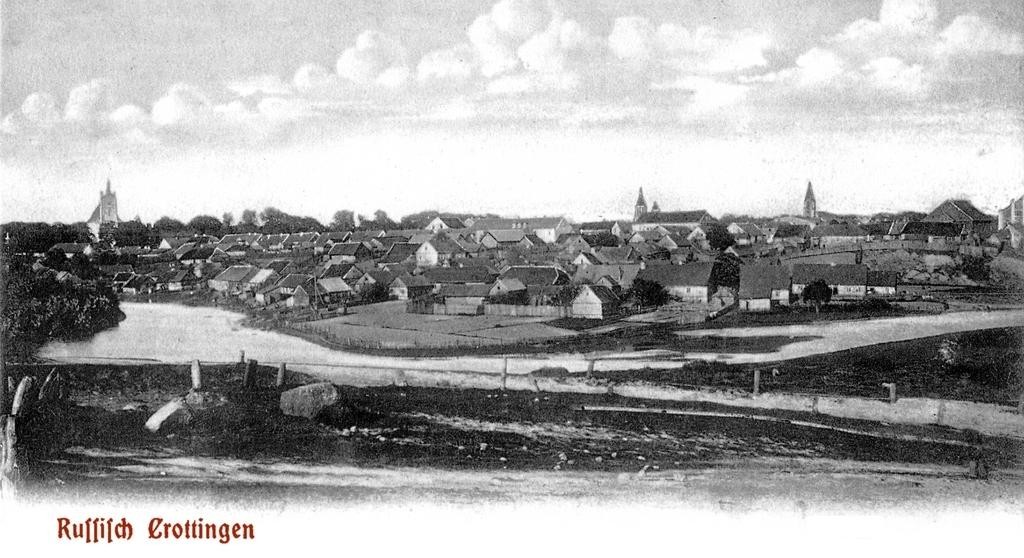

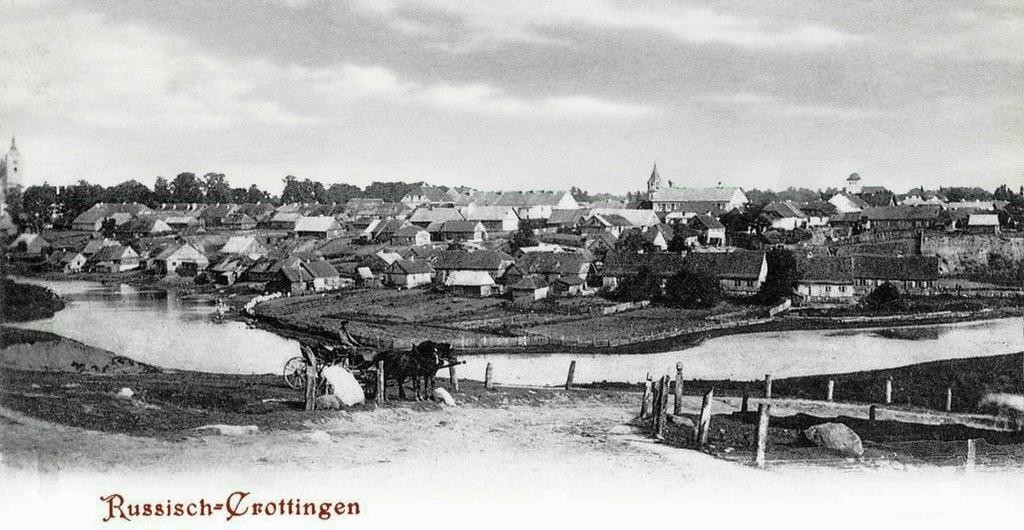

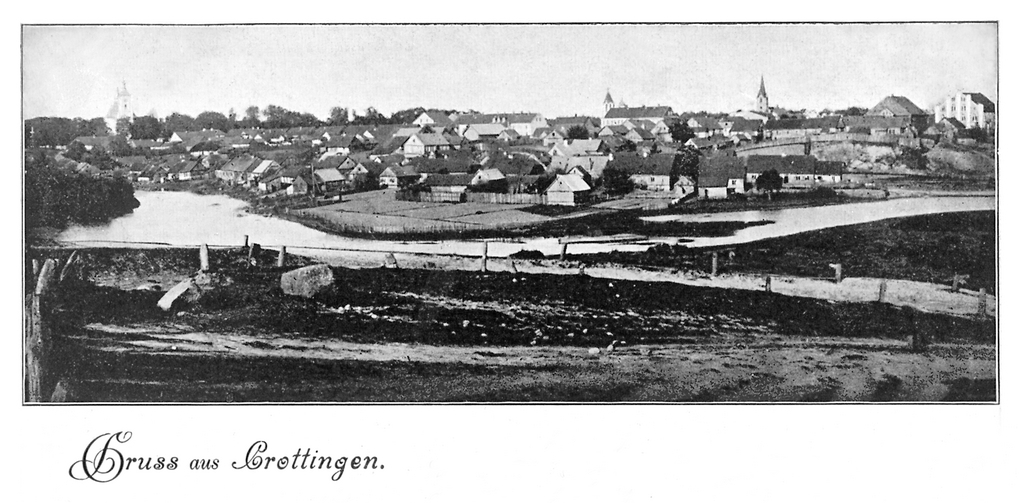

Kretinga is the Lithuanian name for the Shtetl that was home to a Jewish community and to the Gillis family in particular for many centuries. As with many towns in the Pale of Settlement, Kretinga had different names for the various population groups that were either resident or ruled over it. To the Germans is was Krottingen, Crottingen or even Krettingen; to the Russians it was Kretingen - Кретинген; to the Poles as Kretynga and to the Jews it was known either as Kretinge - קרעטינגע or as Kretingen - קרעטינגען.

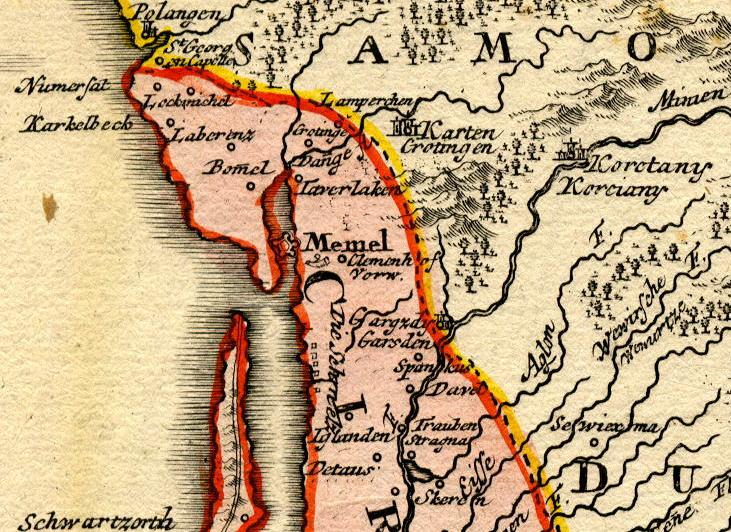

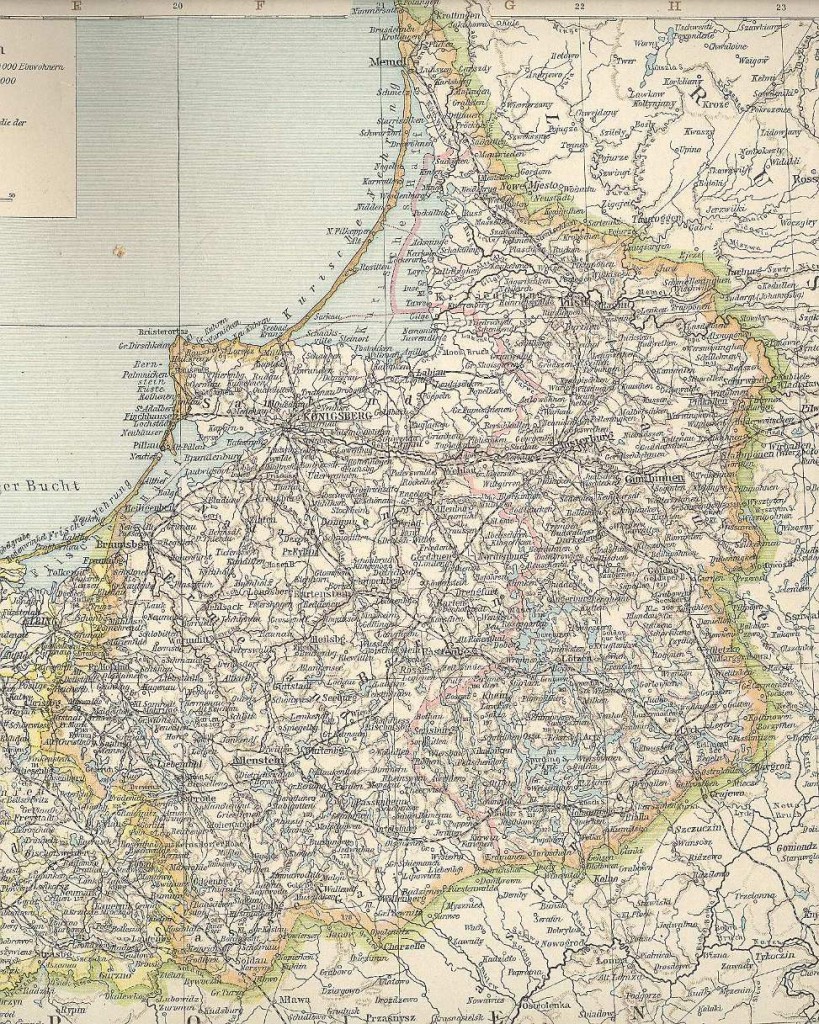

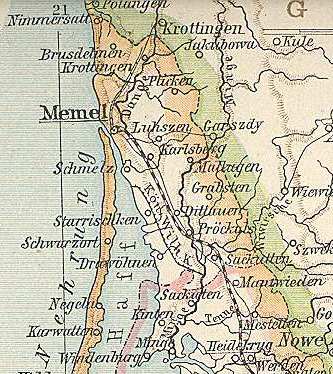

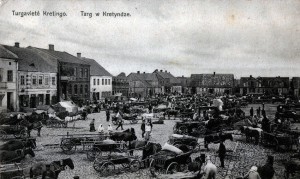

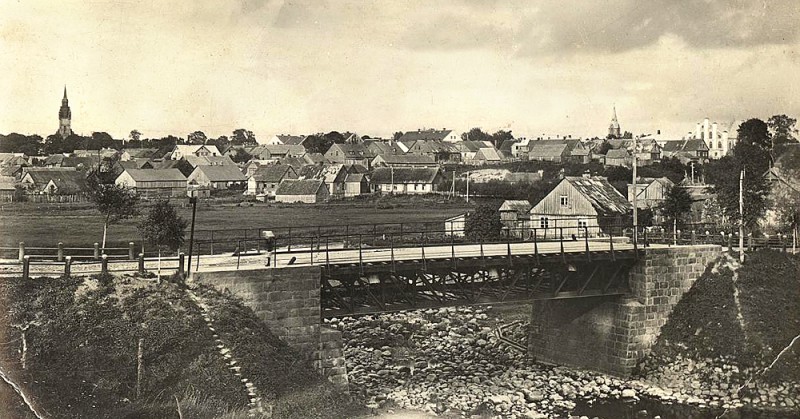

Kretinga is a market town, set on both banks of the Akmena river, some 12km. east of the popular Baltic Sea resort of Palanga, and 25km, north of of Lithuania's third largest city and principal seaport, Klaipėda, a city known to many by its previous name of Memel. Though inside Lithuania, Kretinga's location, less than three kilometers from the former Prussian border, greatly influenced its history, culture and economy through opportunities to establish trading links between Prussia and Czarist Russia.

OriginsKretinga is one of the oldest cities in Lithuania. In 1253 CE the chronicles of the Livonian Order, a military order of German warrior monks, mentioned a castle that was controlled by the Curonians - one of the tribes from which the Lithuanian people would later develop after their adoption of Christianity in the 15th. century. In 1602 Jan Karol Chodkiewicz (Lithuanian: Jonas Karolis Katkevicius) a notable military commander and one of the most prominent 17th. century 'szlachta' of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, built the first church in Kretinga and established a Franciscan monastery. Chodkiewicz named the city 'Karolstadt' after himself, and supervised the planning of the city and the building of roads. In 1607 store houses were established for the transfer of merchandise between Russia and Prussia, Kretinga becoming a major commercial centre of northern Lithuania.

The Population of Kretinga

| Year | Population | Jews | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1663 | - | 3 | - |

| 1847 | - | 1738 | - |

| 1865 | - | 1616 | - |

| 1897 | 3418 | 1202 | 35 |

| 1923 | 2532 | 904 | 36 |

| 1930 | 4401 | - | - |

| 1934 | 4569 | about 800 | 17 |

| 1940 | - | about 1000 | - |

| 1959 | 9690 | 15 | 0.15 |

| 2001 | 21423 | 3 | - |

The 'Poritz' - The Noblemen of Kretinga

In 1609 Jan Karol Chodkiewicz announced that he would establish a new settlement next to the old village and granted the new city 'Magdeburg rights', thus instituting internal self-rule and regulated trade for the benefit of the local merchants and artisans. At the same time this encouraged the influx of Jews who acquired communal autonomy under royal protection. The new city adopted a coat of arms showing the Virgin Mary with the baby Jesus in her arms, which has remained Kretinga’s symbol and patron saint. In 1621 the Sapieha 'szlachta' family gained control of the city; changed its coat of arms to represent Saint Casimir, the patron saint of Poland and Lithuania. Invading Swedish armies destroyed the church and monastery in 1659 and again in 1710, following which the Sapiehas helped to rebuild and improve the structures.

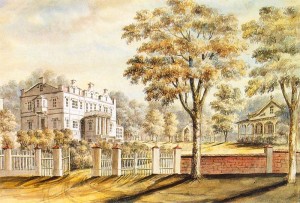

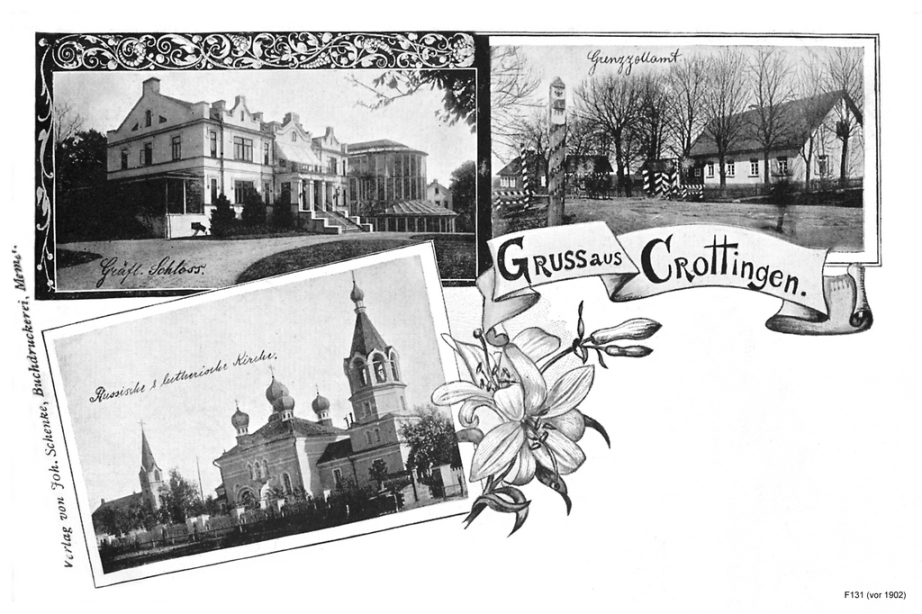

By 1720 the city had come under the jurisdiction of the Massalski family, but lost its municipal rights after the partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. From 1795-1915 Kretinga was under Russian rule and became the regional capital. The estate was acquired by Prince Platon Zubov, a favourite of Catherine the Great. The Zubov's built the manor house, surrounded by a landscaped park. Being only 5 kilometers from the border with East Prussia, the town became the trading centre for whole region. During the initial period of Russian rule Kretinga was part of the Vilna (Vilnius) Gubernia (Region), and from 1843 it was transferred to the Kovno (Kaunus) Gubernia. The feudal or magnate control passed to the 'szlachta' family Tyszkiewicz (Tiskevicius), who attained ownership rights and continued their presence in Kretinga up till Lithuanian independence in 1918.

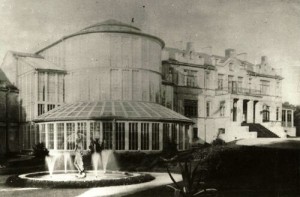

The city prospered during the 19th. century. The first telephone line in Lithuania connected Kretinga with Plunge and Rietava in 1882. In 1875, Count Tyszkiewicz decided to establish his family estate in Kretinga; purchased the manor of the Bishop of Vilnius, Ignacy Jakub Massalski and converted the existing residence into a palace. Following the fashions of the Victorian era, the family landscaped it lavishly to include cascading ponds, a waterfall, arbors, fountains, sculptures, and parterres. A greenhouse featuring exotic flowering plants and tropical fruits known as the Winter Garden was added, one of the only gardens of its type in Eastern Europe. Electricity was they installed in 1890 in the manor. From 1935 the Manor was transformed into the Kretinga museum and orangery; presenting exhibitions on local archaeology, antique sculpture and paintings, the Samogitian house, numismatics, and mementos of the Tyszkiewicz family.

Russian imperial rule was also a period of oppression of minority cultures. Beyond restrictions imposed on the Jews, the Czarist authorities also conducted a policy of Russification, a policy which included the banning of printing of books and newspapers in Lithuanian. As part of a process of national revival Lithuanian publications printed in Lithuania Minor (Eastern Prussia) were smuggled over the border, Kretinga being one of the distribution centres.

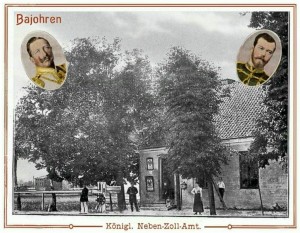

During World War I, Kretinga was occupied by the German army, who built a railroad connecting the customs house on the Prussian border at Bajorai (Bajohren) with Kretinga and the Latvian city of Priekule. The city became a transit point for supplies on the way to the Russian front. Merchants from other areas of Lithuania would come to Kretinga to buy merchandise, hard to find in other areas. With the war’s end a joint committee of Lithuanians and Jews formed to govern Kretinga after the German defeat and the declaration of Lithuanian independence, and in 1924 Kretinga regained its municipal rights and became the regional capital. During the interwar period, the village of Kretingsodis, on the other side of the Akmena River, was incorporated into the city. Kretinga gained greater importance after another railroad was built in 1932 that connected it to Šiauliai, known as Shavel in Yiddish, and on to Vilna (Vilnius).

The Jews of Kretinga

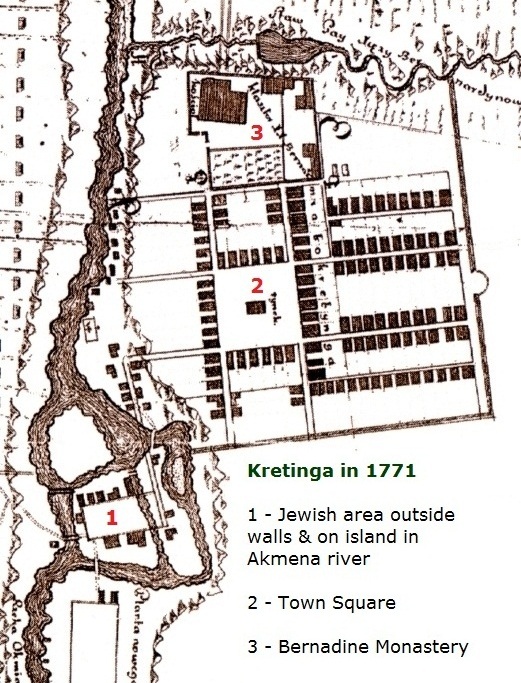

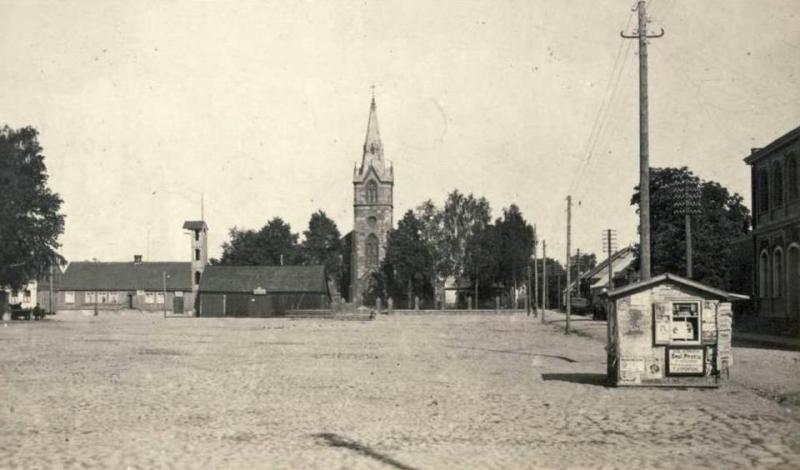

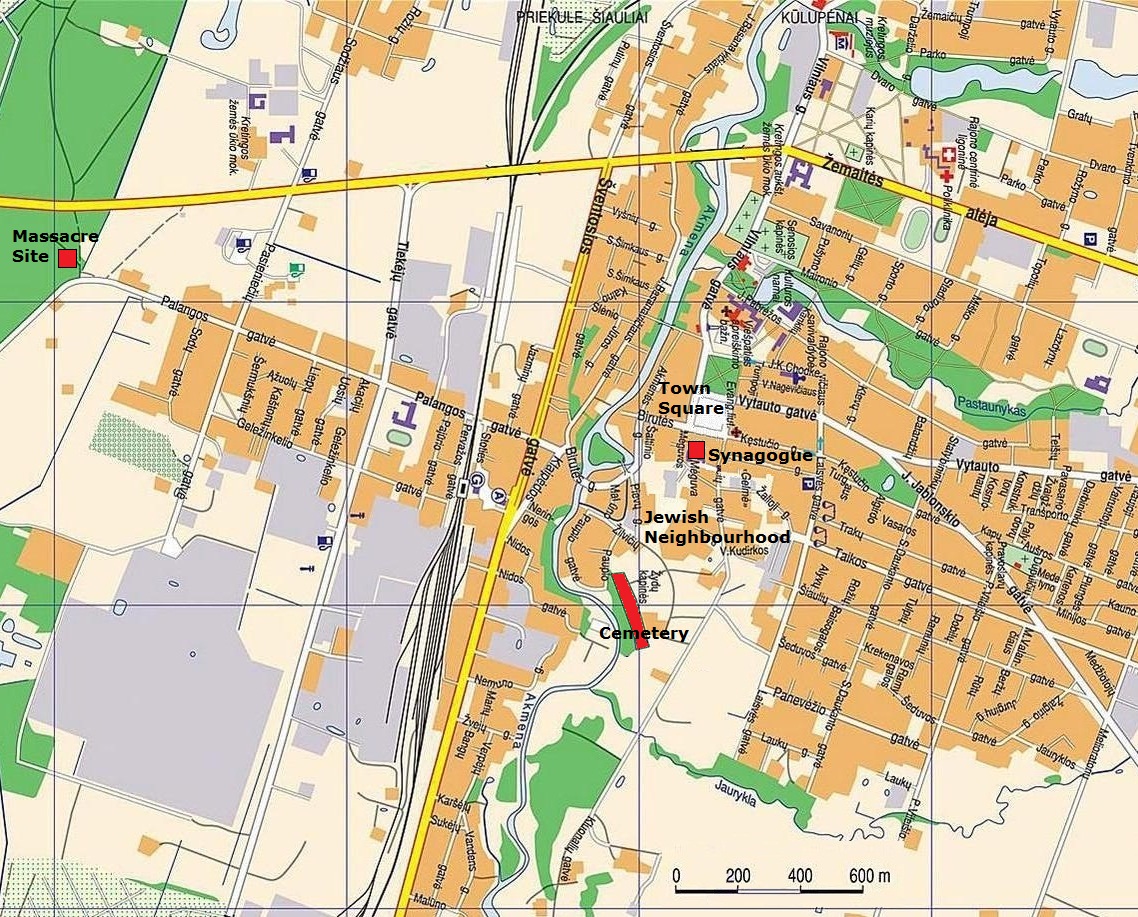

Though Jews were trading in Kretinga as early as the 14th. century but it was not until the beginning of the 17th. century that Jews began to settle in Kretinga. In a census of 1662 there was mention of two Jewish men and one Jewish woman. Jews only settled in greater numbers in the mid 18th. century after receiving special privileges from the Kings of Poland. After the Swedish-Polish wars a Jewish neighbourhood formed beside the Akmena river, to the south-west of the town square. This was a convenient location to partake in the through trade between Memel (Klaipėda) and Palanga.

On an island in the river several Jews established farmsteads set around a small square and operated a water-mill. By 1771 there were 14 Jewish families, totaling 92 individuals. Four Jewish families lived in Vokiečių and Birutės streets in the old part of the city until Bishop Ignacy Jakub Massalski prohibited Jewish residence there, enacting regulations restricting Jewish residence to a specific part of the town, outside the city walls, along Klaipėda (now Mėguvos street), and forbidding them from building or repairing homes in the artisans quarters. Bizarrely Jews were also required to set their facades in the direction of Prussia.

In the 18th. century Kretinga became especially attractive for Jewish settlement, mainly because of its convenient geopolitical location, close to Prussian Memel, with its ice free port on the Baltic, that created opportunities for cross border trade, especially of Russian timber. Though under Russian Imperial rule, the German language became predominant in cross border trade. Thus German Jews found Kretinga a useful refuge during anti-Semitic unrest in Prussia, while Kretinga Jews took shelter in Prussia during pogroms in Russia.

In 1723 a printer named Behr Drucker came to Kretinga from Danzig (Gdansk). Behr Drucker, whose family later took the name Behrman, started in Kretinga as a book seller and later became an exchange broker. His brother Moushe, known as der Danziger, traded in amber jewelry and silver. Under Russian rule, their descendant, Wolf Behrman, was the official representative to the authorities for the Jews of Kretinga. Moshe Levinowitz, also from Danzig, leased a windmill from the Kretinga manor to grind grain. During the eighteenth century Kretinga Jews were involved mostly in small trading - Yosel Solomon traded salt, Leiba Gutman leasing the city water mill and had the brewery, Jankel Issac leased a pub from the manorial estate, Hirsch Yoselowitz owned a store and a brewery and Hirsch Markowitz rented an inn near the village of Šašaičiai. However, these businesses were not profitable and they owed substantial taxes to the treasury. Jews were also active in the trades - such as the well known jeweler Yosel Leibowitz and many others who produced decorative items and jewelry from amber. On the darker side, others utilised their local knowledge of the border area to smuggle goods across the border between Prussia and Czarist Russia. Some Kretinga Jews made their living from small holdings, often raising a single cow or steer, grazing their livestock together with the other citizens under the supervision of a hired shepherd.

Berek Joselewicz - דער ייִדישר קאַמאַנדער

The most famous son of the Kretinga community during this period was Berek (Dov Behr) Joselewicz (1764-1809) who started his career as the financial agent for the local magnate Massalski. In this capacity he had visited Paris and was influenced by the ideas of the French revolution. Joselewicz joined the Polish militia under Tadeusz Kościuszko who had challenged Russian rule over Poland, petitioning Kościuszko to form an all-Jewish unit, which was formed in 1794. Joselewicz, along with Joseph Aronowicz, issued a patriotic call-to-arms in Yiddish denouncing Russia and Prussia, eliciting hundreds of volunteers. A cavalry regiment of 500 men was raised, the first Jewish military formation in modern history. The regiment abstaining from combat on Shabbat, ate only kosher food, and kept their beards for which they were known as the 'Beardlings'. They took part in the 1794 Battle of Warsaw against the Czarist army during which the unit was wiped out. Only a few men survived, including Joselewicz. After the defeat of the rebellion he fled Poland, but later returned as part of the Polish Legion, falling in battle in Kock (Kotsk) in 1809 fighting for Polish independence with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. Joselewicz is still a renowned Polish war hero and is acknowledged by the Israel Defense Forces as the first modern Jewish military leader.

A century after Joselewicz's death a monument was erected on his grave near Kock by a grateful Polish nation. The epitaph reads:

Berek Joselewicz Józef Berko vel Berk, born in Kretinga, Lithuania. The colonel of the Polish army, commander of the squadron of the 5th. Mounted Rifle Regiment of the Duchy of Warsaw, Knight of the Crosses of the League of Military Honor, died in the battle of Kock in 1809. This is where he is buried. His road to fame was bloody, unlike others who cheated and drank from their quarter pocket-bottles. In remembrance of the 100th. anniversary of his death.

A monument to Joselewicz, known in Lithuanian as Berekui Joselevičiui, was unveiled in Kretinga in 2015.

Under Russian Rule

A description of Kretinga from the early 19th. century lists 28 crowded Jewish houses with 120 inhabitants from a total of 111 houses with a total population of 435. Also listed is a synagogue on the road to Memel and a number of brick buildings, two belonging to Jews, including the stone house of Leib Sapir opposite the town hall. As the city developed the Jewish community continued to grow and congregated in the centre of the town. A Kahal council autonomously administered the community, representing the Jews of Kretinga and the surrounding villages to the civil authorities.

In 1843 Czar Nicholas I ordered the expulsion of the Jews from a strip of an 50 versts (around 50 kilometres) along the border its western border with Prussia and Austria. Kretinga was one of 19 communities that did not respond to the order and in fact a reverse process is evident. Jews, also restricted from the working the land, prospered in the trades and crafts. Jews purchased timber, flax, grain, poultry and meat from the Lithuanian farmers for trade in nearby Prussia. Jews were also prominent as taverners, restaurateurs, shop owners and in transportation. By 1868 Kretinga had 2,573 residents,1,509 of them of Jews (almost 59%) living with 438 Catholic Poles and Lithuanians (17%), 362 (14%) Orthodox Russians and 263 (10%) Lutheran Germans.

In 1855 a fire razed many of the community homes and the only synagogue. It was rebuilt in 1860 with a 15,000 ruble loan, only to burn down again in a huge city fire in Shavuot 1889, together with the Beth HaMidrash and the Kloyz. An appeal for aid published in HaMelitz led to a Kretinga Relief Fund being established in Sunderland, where a community of emigrant Kretinga Jews had been established.

Kretinga was considered one of the most important trading centres in the region, with many businesses concentrated in the hands of Jewish and Prussian merchants. The largest traders of the period were Hirschowitz and Katznellenbogen, who had set up the store to trade foreign wines and spirits. Many Jews worked in business, trading on both sides of the border and earning their keep as customs agents. Others were shop owners and tradesmen. Furthermore, the area of Kretinga and Palanga was well known for its amber. Some Jews processed the amber, while others sold the product on in Russia and around the world. Jewish arts and crafts factories made amber jewellery for sale to the summer tourists, especially in the nearby seaside resort of Palanga, where a Museum to Amber has been set up in another palace of the Tyszkiewicz family. The family name Bernstein, meaning Amber, was a common surname among the Jews of Kretinga.

Mass emigration from the Kretinga and the Memel area had begun in the 1870s to the United States, South Africa and the United Kingdom. Many, as previously stated, settling in Sunderland on the north-eastern coast of England. The first recorded Kretingerer in Sunderland was Barnett Bernstein, an escapee from the Czarist army, arrived there in about 1859 and was related to the Gillis family. In a list of emigrants of 1869/70 were the Kretingers, H. Benion, Y. Ber, H Bernstein, S. Gallewski, M. Shergei, D.A. Olswang, Israel Harris, Charles-Yechezkel Gillis and Y. Pearlman. These family names became intertwined with each other through marriage. Many of these immigrants were instrumental in forming the Relief Fund after the fire in Kretinga in 1889. This emigration had a huge demographic effect on the community. In 1847 there were 1,738 Jews in Kretinga. By 1897 this had dropped to 1202 out of a population of 3418 (35%). By 1923 there were 904 out of 2532, and before the Holocaust only 700.

Cemeteries

As the Jewish population grew, two cemeteries were dedicated in Kretinga for the community. The first cemetery, now lost, was located beside the Lutheran cemetery on the Gargždai road. The main cemetery, covering 13 hectares, is situated south of the synagogue on Mėguvos street, on the east bank of the Akmena river. This cemetery would become one of the mass murder sites of the Jewish community during the Holocaust.

Today the only visual reminder that there was ever a Jewish community it Kretinga is, symbolically, the cemetery. Fortunately, in the past few years the municipality and local volunteers have aided in the upkeep of the cemetery, clearing vegetation and cleaning the matzevot (stones). The Jewish cemetery of the lost community of Kretinga has been declared a national monument and the 356 surviving matzevot have been documented.

Jewish Cemetery in Kretinga

Community Life and Zionism

The social life of Kretinga’s Jews concentrated around the synagogues, located on Klaipėda (now Mėguvos street), known in Yiddish as the the little 'Shul' Gass. Along side was a Beth HaMidrash, in which Gemarrah (Talmud) studies were held. A Mishna Society operated in the old Kloyz (small synagogue) and the Chevra Tehillim (Psalms), mostly of trades people, operated in the little Kloyz. Even with their declining numbers the community appealed in 1892 to the authorities with a request to permit the construction of a second synagogue due to lack of space and by 1906 a second synagogue stood in the town. Kretinga's Jews were observant and produced a series of scholarly rabbis in the Litvak-Mitnagdim tradition including Rabbi Menachem Mendel, who came from Prague in 1648; Reb Aharon Kretinger, who died in 1842 and authored the book 'Tosfos Aharon'; Rabbi Aryeh Leib Lipkin, nephew of the Salanter Rabbi, who officiated between 1878-1902, and wrote 'Divrei Yedidya' and 'Or Hayom'; and Rabbi Shmaryahu-Yitzchok Bloch, born in Kretinga, who became Rabbi in Sunderland in 1894 and Birmingham in 1902.

Beside the traditional cheder, in 1860 a Jewish School was established, where Jewish studies, maths, Russian and German were taught by Aryeh Leib Shapira. In 1910 a private Jewish School was established for boys with two classes.

Zionism was strong amongst the Kretinga Jews from the early years of the movement. Yoel ben Eleazar Drubin, born in Kretinga in 1857, was among the first Biluim. After high school he emigrated to Eretz Israel, becoming was an agricultural worker and then a farmer in Rishon le-Zion. In 1911 he took part in a delegation to Baron Edmond James de Rothschild in Paris to renew his commitment to the colonies, Rishon le-Zion and Zichron Yaacov. Most however demonstrated their Zionist commitment through fundraising for settlement, a fact noted in lists of donations registered in newspapers of the time. In advance of the fifth Zionist Congress of 1902, 200 shekels were sold in Kretinga indicating a deep attachment to the Zionist cause.

Voting in the Kretinga Community for the Zionist Congress between 1925 to 1935

| Zionist Congress | Year | Sheqels | Votes | Socialist Zionists | Revisionists | General Zionists | State Zionists | Mizrachi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | 1925 | 40 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 15 | 1927 | 92 | 46 | 7 | 8 | 28 | - | 3 |

| 16 | 1929 | 224 | 97 | 14 | 17 | 51 | - | 15 |

| 17 | 1933 | - | 248 | 131 | 34 | 40 | 5 | 38 |

| 18 | 1935 | 439 | 370 | 176 | - | 59 | 2 | 133 |

Independent Lithuania

The First World War started with a further conflagration which again destroyed large sections of the town centre. Kretinga was occupied by the German army from the beginning of the war, becoming a transit point for supplies on the way to the Russian front. Merchants from other areas of Lithuania came to Kretinga to buy merchandise hard to find in other areas. At war's end a joint committee of Lithuanians and Jews formed to govern Kretinga after the German defeat, prior to the declaration of Lithuanian independence.

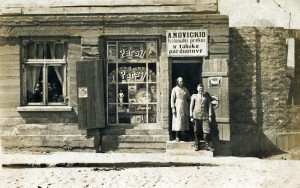

Jews continued to be trade and craft leaders in the town. Like in the majority of Lithuanian towns, Jewish business, marketing and residence focused in the urban center and in the surrounding streets. Kretinga's Jews centred mainly in the south of of the town, especially in Vytauto, Birutės, Kartenos, Gargždų, Daržų, Pirties, Palangos, Turgavietės streets. One of the most important entrepreneurs of the period was Judel Teitz who, together with E. Sher set up a tea, saccharin and candle factory on Birutės St. marketing their products under the name Virdulys (Teapot), Švyturio (Lighthouse) and Malūnas (Windmill).

The Kretinga Merchants and Industrialists Union was set up by Nachman Shpitz, Nathan Resnik, Meir Schwartz, Hirsch Tubianski and Savel Israelowitz, an initiative that did not include Teitz and Sher, the largest industrialists in the town. On the opposite side of the capital divide, socialist Jews established a workers union in 1920, headed by Shaul Leiba Peretz. In the same year, the 'People of Israel Workers Cultural Association' and the Zionist socialist Ber Borochov association were founded. The kehilla (community) organised itself to administer Jewish matters under the autonomy rule for Jews under the auspices of the Ministry for Jewish Affairs of the Lithuanian government. A committee was appointed comprising 6 General Zionists, 3 Zairei Zion, 3 workers and 3 unaffiliated. The committee managed the affairs of the Jews of Kretinga, and for a short time was responsible to issue travel documents for those traveling to the Memel, which was occupied by the French under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles at the end of WWI. This resulted in the accumulation of large sums for the Community committee. The practice was abolished when Lithuania unilaterally occupied Memel-Klaipeda in 1923.

Jews were also regularly elected to the city council. In 1924 five of the 15 representatives, including the deputy mayor - Pesach Zegerman, were Jews; the number dropping in later years due to emigration. For a city so prone to damage by fire, as most of its buildings were constructed of wood, Jews were also prominent is establishing the volunteer fire force in 1907. The fire station was built in the town square.

As in the pre-war years, the rebuilt Synagogue, Beth HaMidrash and Kloyz were the centre of religious life in the city. Rabbi Binyomim Persky was the last Rabbi of the Kehilla before being murdered in the Holocaust. In the city there was a group of 'Tiferet Bachurim' and a children’s group 'Pirchei Shoshanim'. Relief agencies in Kretinga included 'Gemilus Chesed' and 'Bikur Cholim'. All the Zionist parties and the religious non-Zionist Agudat Yisrael party were represented in the town, their involvement growing in insensitivity through the years of Lithuanian independence to include a large percentage of the Jewish adult population.

Gathering Clouds

The economic depression of the 1930s affected Lithuania, leading to the rise of the antisemitic Lithuanian organisation of merchants (Verslas) who called for the boycott of Jewish traders. Furthermore, the proximity of the pro-Nazi Germans in Memel strongly influenced the growth of anti-Jewish feeling across the border in Lithuania. With the rise of Lithuanian nationalism the relationship with the Lithuanians deteriorated. In the winter of 1928 tar was smeared on Hebrew and Yiddish shop signs and in 1936 there was a blood libel that was repressed by the authorities. The entrance of the Benedictine nunnery displayed the sign, "Entrance to strangers and particularly to Jews is forbidden". This led many to look elsewhere for their future and in 1935 the Jewish Folksbank was forced to sell the building. In turn, some of the Jewish youth joined the communist underground. A military tribunal in 1935 tried Ber Persky, son of the Rabbi; Leib Gillis and a Miss Share to long prison terms for concealing pamphlets of the banned Communist party in the Beth HaMidrash.

Still, in 1939, a government survey showed that of the 77 shops in Kretinga 64 were Jewish. Furthermore 18 of the 26 factories in the city had Jewish ownership, including the power station and two workshops for amber products. Other small Jewish businesses and professions included butchers, bakers, tailors, hairdressers, milliners, tinkers, carpenters, smiths, shoe repairs, a clockmaker, wool carding, tile manufacture, a taxi company, books, office supplies, ironmongers, dry goods, groceries, paints, cosmetics, electrical goods, lemonade manufacture, oil lamps, blacksmiths, three dentists and a doctor (Dr. David Karlinski).

| Retail Branch | No. of Businesses | Jewish Owned |

|---|---|---|

| Grocery | 11 | 11 |

| Grain and Linen | 2 | 2 |

| Slaughterhouses | 14 | 13 |

| Restaurants and Inns | 3 | 0 |

| Foodstuffs | 12 | 12 |

| Milk Products | 1 | 0 |

| Cloths Furs and Textiles | 5 | 5 |

| Leather and Shoes | 4 | 4 |

| Pharmacy and Cosmetics | 3 | 2 |

| Watches Amber Products | 2 | 2 |

| Industry Branch | No. of Businesses | Jewish Owned |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Electric Power | 2 | 2 |

| Grave Markers Bricks Concrete | 2 | 1 |

| Chemicals: Spirit Soap Oil | 2 | 1 |

| Textiles: Wool Dyer Looms | 1 | 1 |

| Wood Bitumen | 3 | 2 |

| Food: Mills Bakeries | 10 | 8 |

| Clothing Shoes Hats | 4 | 1 |

| Others: Bristles Amber | 2 | 2 |

| Wood for Heating | 1 | 1 |

| Paper Books and Stationary | 2 | 0 |

Tables showing the economic status of the Jewish Community in Kretinga in 1939 based on a Lithuanian Government survey of business.

The situation deteriorated further after the Nazis annexed Memel in March 1939. The Jews of Memel became refugees and the Kretinga Jewish community absorbed 300 of them. Following the Molotov Ribbentrop Pact, Lithuania was occupied by the Soviet Union, who immediately nationalised the factories and the retail trade, which had remained largely in Jewish hands. All the Zionist parties and youth movements were disbanded and the Jewish educational institutions were closed. The availability of commodities shrank and prices shot up. The Jewish middle class was heavily affected, and seven ‘undesirable’ Jews were exiled to Siberia in June 1941 together with many Lithuanian citizens. However many Jews welcomed the new rulers and took an active part in its institutions which viewed, correctly, as as greatly favourable to Nazi rule.

The German Invasion and the Holocaust

Operation Barbarossa, Nazi Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, commenced on June 22nd. 1941. The Germans 61st. Infantry Division, entered Kretinga on the 24th. June 1941 without any opposition. Immediately the Tilsit Einsatzgruppen went into action, murdering the first group of Kretinga Jews within two days of their entry to the city. By August 1941 the Kretinga Jewish community has ceased to exist! These murders, together with those perpetrated in Palanga and Gargždai, were the first committed by the Einsatzgruppen in the Baltic countries, Ukraine and Russia and would end with the destruction of Lithuanian Jewry, the loss of 1.4 million Jewish lives, of magnificent historic communities and their physical heritage. A full description of the Holocaust in Kretinga can be found here.

Kretinga after the War

After victory in 1945 the Soviets started to undertake reprisals against Lithuanian nationalists and those sections of Lithuanian society that had collaborated with the Nazis. This led to further reductions in the population of Kretinga, as refugees, especially collaborators, fled to the west while close to 400 of those trapped, together with a large group of Lithuanian anti-Soviet nationalists were deported to Siberia. Few Jews returned and the community never recovered. Under Soviet rule Kretinga became an economic backwater, the collectivisation of the farms being particularly difficult for the Lithuanians. However, since Lithuania's independence in 1990, the town has made a recovery and now forms part of the tourist route along the Baltic coast. From the information provided by the municipality, Kretinga is proud to host folk music festivals, theatricals, the Kretinga Festival, celebrations on Midsummer Night's Eve and a Manorial Feast, based at the Kretinga Museum. The city has also built a powerplant to exploit the heat generated by the Cambrian geothermal reservoir under its surface.

In recent years preliminary, though significant, efforts have been made to maintain the Jewish cemetery and massacre site and to raise awareness of the fact that Kretinga was until only seventy years ago, a town with a fifty percent Jewish population. Recent activities have included the clearing of the cemetery, the unveiling of a memorial to Berek Joselowicz and the excavation of a miqve near the town square. More needs to be done to, including the establishing of a suitable memorial to the Jews of Kretinga in the Town Square, but an understanding that half of the population of a town like Kretinga cannot disappear without commemoration is slowly being acknowledged.

Some Views of Kretinga Today

Yizkor - A memorial page for the victims of the massacres of the Jewish community of Kretinga between June and October 1941 can be found here.

Sources

This article is based on a series of articles that use original documentation as their factual basis. Please feel welcome to contact if you wish to correct or augment the information.

1 - There are a series of Wikipedia articles. The central article on Kretinga will point you the to the rest, though like almost all articles originating in Lithuania, the past existence of Jews in their midst is sadly ignored or only noted in passing.

2 - Kretinga. In. Dov Levin. 1996. Ed. Pinkas Hakehilot: Lite. Yad Vashem. Jerusalem Pp. 617-621. (Hebrew).

3 - Shtetl Links - Kretinga

4 - Arnold Levy. 1956. The History of the Sunderland Jewish Community. Macdonald. London.

5 - Ieva Malukiene, Agne Rymkeviciute, Rita Satrovaite, 2007, Kretingos miesto Ikurimo istorija. On the Jews in Lita website.

6 - Kretingos krašto enciklopedija website (Kretinga Online Encyclopedia in Lithuanian.)